The story of one teacher's leveling up experience, and the benefits that followed

An Expert-level middle school math teacher, Charity Rock, shared her experience in leveling-up to the Expert-level and the benefits that followed.

I’d been teaching for about a decade in California. I’d always pass by one middle school in our district and think, “Oh my gosh, I’m so happy I don’t work there.”

Then I was placed there.

Teaching 8th grade algebra.

At Washington Middle School.

We were impoverished. We had homeless students. We were in the middle of a desert of crime. Our whole school’s suspension and absentee rates were dire. We had every indicator that our school needed help. Absent students got support, but there wasn’t a pre-planned system.

I was so upset to be placed there.

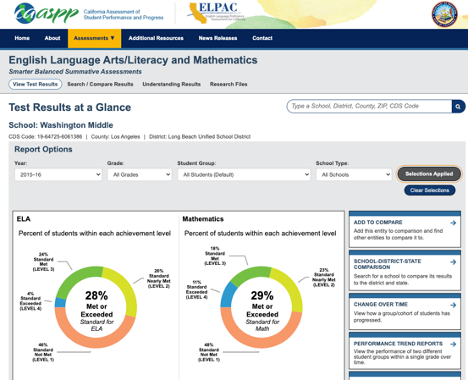

We were the lowest performing school in the district. In my first years, we had district end-of-the-year assessments. Those were common across all schools, but we didn’t necessarily see each other’s scores. The scores weren’t broadcasted. It was very individualized data sharing. I saw class scores and was like, “Okay, my kids are doing fairly well.” My students’ scores weren’t where I wanted them to be, but they definitely weren’t terrible.

I think I arrived at this very fluke-ish time for assessments. I don’t remember getting any jarring numbers. I was in my own private classroom, so I thought everyone was teaching similarly. In our team meetings, I don’t even know if I had an agenda. I think perhaps we were talking about the kids. Maybe we were talking about what was coming up next. It started. It ended. Have a good day! I don’t remember any time going into planning any of my department meetings, nor do I remember being pressed for time. I don’t think it was even that department specific.

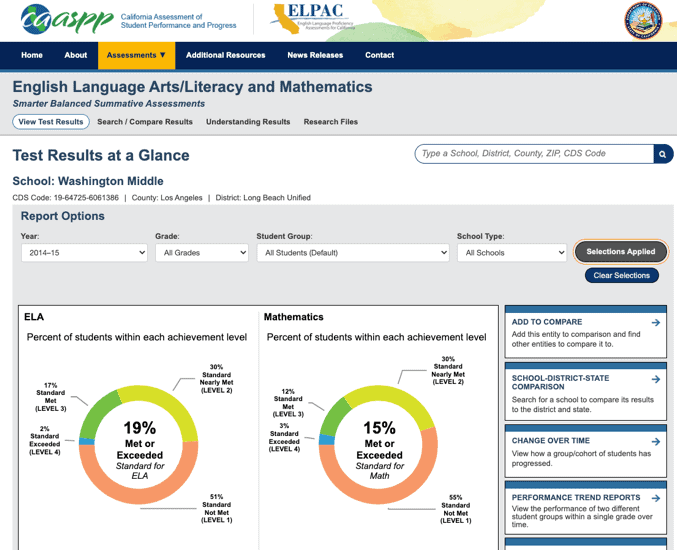

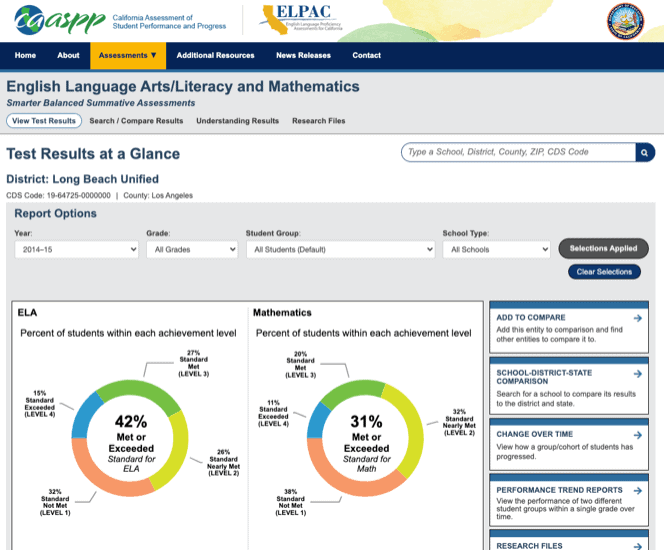

We had previously had the Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) test. Then we were in a transitional phase, we went maybe two years without a state test. Then, they introduced CAASPP, so it was preliminary, and the scores didn’t “count.”

But…

Our first year, we were about 15% proficient. We were the lowest performing school in the district. There were a couple super high performing schools. The average was about 30% throughout the district. We didn’t get the data until the end of the school year.

I was shocked. I was so sad.

That’s when I said:

“Nope.” I was like, things have to change.

Business as usual wouldn’t cut it.

I had an opportunity to see that students can’t study their way into doing well on the CAASPP. They can’t memorize every single question. Students must know how to think critically and unpack a question so that every time they see a new one, it makes sense.

Professional Epiphany

I had been a really precise teacher. I was so clear. I could explain anything and make it make sense. I used to get great feedback. I would have visitors come and say: “Wow! You’re great! Your kids are engaged.” I didn’t have too many students absent in my class, so that wasn’t a major issue. I can’t recall how my students performed, but they weren’t as bad as the school’s overall 15%.

However…

I received feedback earlier in the first year of CAASPP. It was my principal’s first year taking over as the principal. She was accompanied by about four district-level folks to observe the teachers and provide feedback. At first, they debriefed us. Then, whoever’s classes they visited, we would go in and get feedback from the group. It was verbal, but I’m sure they wrote things down somewhere. I was ready to receive all the good laurels because I was teaching the heck out of it. I would ask myself a question, then I would answer my whole question. I was just on it. I was on such a high because I thought I was about to get this good feedback again. I’m sure I had a book that I read about CAASPP, but I was like: “I’m already doing this. I’m good to go.”

Then they told me I talked too much

and didn’t let the students think for themselves.

I was stealing all the thinking from my students. The feedback was: “You explained it great, but the students didn’t say a thing.” You’re still teaching the old-school way. Some students understood the topics because I explained things so well, but I didn’t give them enough time to think about the problems, make mistakes, fix their mistakes, and collaborate. I didn’t offer that space in my classroom.

I don’t even know how I responded.

I know I was shocked, which has stuck with me.

I had never received negative feedback before.

I was known as a wonderful teacher, but I respected the group’s feedback, and I respected my principal. They had been trained on the new CAASPP standards, what it entails, and all the questioning involved. They were all in agreement about my feedback. I couldn’t deny what they said.

Talking too much was the feedback that really shifted things for me. I’m so grateful for it, but in the moment, I was like: “What the heck?”

I was pumped up. I turned that sadness into pure energy, like: “We got this. Let’s just do it.” I started making shifts on my own. No one else necessarily did.

This was me developing into the teacher I am now.

Student Learning Focus

For me, the biggest piece was stepping out of the way of the students. The secret formula is: “Get out of the way, ask questions, and let the students experience it.” That’s it. They’ll get it. I put big signs on my board to remind me and the students of this.

One sign said: “Who is doing the thinking?”

That’s a powerful statement and question. I think about that as a teacher in everything I do—every plan I make, every implementation of the plan.

Another sign said: “Not the fast answer. The thoughtful answer.”

For that to really unfold, the teacher must facilitate the class in such a way that we are saying, “Slow down. Everyone has two minutes of think time. Jot down what you’re thinking.” Those small implementations allow students to access the information before someone says the answer. The shifts in our lesson planning, co-teaching, looking at assessment data, and teaching practices promoted protected, independent think time in all classrooms. Everyone had an opportunity. We were also looking for students to jot down what they are thinking, so when it’s time to turn and talk, they have something to say, and they have something tangible to refer back to. It’s also important to have opportunities for students to revise their work.

Regardless of the activity, the most important thing is protected, independent think time. I was conscientious of how much time students needed to work independently and what I was doing when they were working independently. I was circulating and jotting down what kids were struggling with, the different answers, the different strategies, and the mistakes. Then, I grouped kids based on their work. Some teachers think independent think time is for after you teach them. That’s practice time. You want them actively thinking throughout the entire lesson.

The biggest thing is teaching students that

individual thinking is honored and protected,

regardless of what type of project they are working on.

Even when students took notes, I had them fill in notes, so they weren’t wasting time copying stuff down. There were so many questions posed in the notes, like “What do you think you should do next? What does this mean?” I gave them 30 seconds to think and 30 seconds to talk to their neighbor.

Kids were thinking for themselves, talking about it, and revising it.

I never just told them what to do and what to think.

Classroom Environment

I didn’t have any disruptions. I knew what it felt like to be a middle school kid and a person in general. You don’t want to just sit down and listen. I tried to be as entertaining as possible because I had to entertain myself, too. I also knew what came out of my mouth was of value, so I never spoke when a class was speaking. I didn’t have any management issues.

I loved the kids.

They loved me back.

It is a mutual, really good relationship.

Huddles

We would do ‘huddles’ in class. I would give the students a high rigor task and give them five minutes to work on it independently. After five minutes,

I had students meet me in the hallway if they were done.

If they hadn’t finished, I told them not to rush and to keep working. In the beginning, like seven students would come out. My classes were packed. It wasn’t legal, I’m sure. Sometimes I had like 42 students because kids said they wanted to be in my class, and I would take them.

If I had a small group outside, we would look at the answer and whisper it together, like “What did you get for number one? How did you get it? When I walked around, a lot of kids have 4. Why do you think they have 4?”

I coached the kids to be master questioners.

Then, I had the small group kids go to someone sitting down and ask them questions. At the end of the class, every kid had one-on-one support and got to talk about the problem with someone else.

I got to a point where I said,

“Hey kids, do you like when it’s just me, or when it’s one-on-one?”

Sometimes, the entire class would meet outside the classroom. Over time, the kids could unpack never-before-seen problems because they had their own toolboxes.

I remember getting another big visit from the district. This time, I was in full swing. When they left, I thought, “I didn’t do anything, but that’s how my class runs now.” They said, “Wow, your kids have taken ownership of their classroom.” I lesson planned very well and very thoughtfully, but the kids read it themselves. They were asking each other questions.

I was just facilitating.

It was amazing.

Huddles became a daily strategy my second year. It shifted the way I created my lesson plan because I had a lot of time. I thought to myself, “What are the things they need? What is a big task that I can create space for them to do what they learned?”

Curriculum: Planning

I was thoughtful, making tweaks, realizing what was going on, getting those drastic test scores, spending the entire summer thinking: “Our kids don’t know what value means, that formula means nothing to them, let’s have these hands-on projects where they’re measuring, let’s do all of these things…” My students had done well on quizzes overall. They were learning, but it was not internalized. I had not intentionally spiraled all the power standards.

I just moved from one unit to the next.

I prepared the entire year’s sequence and spiraled these standards across classrooms, so the students wouldn’t forget what they learned. They saw problems every week, so it wasn’t lost to them (i.e., Pythagorean Theorem problems every Monday). Use it or lose it.

I knew how much time we had, and I knew our goal, so I selected which problems we were going to do and how we were going to implement it.

It’s all about putting in the work to unpack the curriculum yourself

and recognizing what parts of it you’re going to use.

Make sure it’s implemented in a way that the students are thinking and considering what’s in front of them versus just showing them.

I was still very thoughtful even back in the day about sequencing, but I was not thoughtful about the experiences the students had and upping the rigor of the task in front of the students.

Curriculum: Problems

The curriculum included a lot of practice problems. CAASPP released practice problems, and I love creating math tests. I’m always thinking of things. I thought about the common experiences the students needed across grade levels and what types of daily exposure questions needed to be asked.

We couldn’t do everything. Curriculum is important and there is a lot of it. There are more problems than you need. What comes in handy is being very selective as a teacher and asking yourself: “What’s the goal of this lesson? What’s going to get me there?” We have 45 questions and five example problems, but we can’t do all of that. We also have higher rigor word problems.

We did a lot of level tasks. There could be scenarios that weren’t very in-depth, but you could ask students: “What questions could be asked from this? What information do you have? What question could be attached to this?” Having the kids doing the thinking and creating these questions as well.

Curriculum: Projects

I spent the summer thinking about the alignment between 6th, 7th and 8th grade,

and certain hands-on projects we need all of our students to do.

I created a hands-on project sequenced for 6th, 7th, and 8th grade, so each grade they experienced a project. The rigor increased each grade, and the standards matched the grade-level standards. The projects were pretty fantastic.

Bedroom Carpet

There was one particular big project. There was a map of a home with different bedrooms and little squares (tiles). The students had to first, on paper, think about the square footage of the carpet needed for two of the rooms. I included the price per square foot at different stores. Some stores had a discount. It was a very layered problem. At the end, the students had to determine exactly how many square feet of carpet they needed, and which store they should purchase it from. I also included a coupon, which made the carpet cheaper, so they had to include their reasoning for their answer. I actually found the stores online, so they could go and shop for it. It was a real thing.

There was a lot of independent time for that project. They would go in their groups and compare their answers. They would try to come to a consensus, but the ultimate consensus was not from me. It was the real-world answer. It was fantastic. At the end, they proved themselves and learned how to cover the space of something.

Swimming Pool

I’d never stressed geometry too much, but I realized they weren’t memorizing the formula and they weren’t getting the units correct because they didn’t know that volume is 3D capacity versus area. It meant nothing to them. They just guessed. Geometry is a real-world thing, so I set out to bring geometry problems to life (i.e., swimming pool cubic inches).

I had a similar layered problem with a swimming pool. The students had to convert the gallons to teaspoons. Then, they measured the water in a measuring cup. If the measurement was correct and the water filled the cup perfectly to the top, you could see the kids’ excitement. The project included converting units, measurements, and recognizing value. I also included something like chlorine price, so they chose which is the better deal.

I remember one teacher said: “This is fun, but I’m not doing it in my class. It’s going to get too wet.” I said: “Oh, yes you are. This isn’t for you.” She said, “Yes, mother.” This stayed in my head because I had to realize you have to respect students that are in different places, and teachers are in different places, too. The way that asked teachers questions changed. I grew a lot from that experience.

I wrote these projects from scratch over the summer. It was a lot of work, and it was for 6th, 7th, and 8th grades. I created each of these with a standard attached. For 6th grade, they didn’t have fractional edges, they had squares. There was a triangle in one of them because that’s a 6th grade standard. Once we reached the other grade levels, the shapes and figures were irregular and fractional. Project timing depends on sequencing and how the students were doing. For 8th grade, we did it around the same time. 6th and 7th grade might be a little different, but we were all doing it. We had to have flexibility with students and teachers. Ultimately, I wanted to make sure they were not just doing the project at a certain time because everyone else was doing it. It needed to make sense, so it did not always work out that the entire school from 6th to 8th grade was doing a project at the same time.

At the end of the projects, no matter what the students did in collaboration, there had to be proof that they could do it independently. So, there was some form of an independent exit ticket attached. This was different, and it was more time sensitive, but it showed that they could do it on their own.

When we did the projects, we brought them to our department meetings and let teachers know what the students learned from it, what worked, and what the student data looked like.

Managing Time

These projects occurred in one day. I could stretch them out, but I didn’t have that kind of time.

We had urgency.

I would say something like: “You have 12 minutes to independently do this. You have another six minutes to get with your group.” Time was real. I had to give them time structure. For middle school kids especially, if you tell them to work on something but don’t give them the amount of time, they have no compass. Say: “You have two minutes to unpack the problem. Go!” Then, “You have six minutes to come to a consensus. I need to hear a lot of talking. You got it!” Tell the students, “We’re doing this whole project in 60 minutes. Can we do it? Yes!” I’m very precise. We’re not stretching anything out across weeks. We can come back and revisit.

Saturday School

We had focused Saturday schools where we would invite specific groups of students for particular standards. When I introduced all these pieces, it was very focused and precise. Saturday school was new. We also had the summer bridge to get kids on an accelerated track or get up to speed on material. It was focused and short (about four weeks). Kids could to continue to grow wherever they were. There was one per grade level. I was teaching 8th grade. I would take any student; they didn’t have to be in my class. Saturday school focused on one standard. We did a mini test, huddles, and an exit ticket. We had about two and a half hours. We would start off with a little snack, then, we jumped into the work. It wasn’t so different than a usual class, except it was very hyper focused on one topic.

Students volunteered to come to Saturday school.

They knew it would help them improve. It was not punitive. They didn’t have to come to every Saturday school. Sometimes they didn’t need it. I had some students who just wanted to come, and I would have them be assistants. Parents were not resistant to Saturday school at all.

Student Agency

One big piece was student awareness data.

It was up to the students to keep track of their own data.

The goal was, you could stop any kid in the hallway and say, “What was your score on the assessment last year? What’s your goal for this year? How many points do you need? Are you getting there?”

How many kids knew this information versus

how many kids didn’t know it,

was a piece of data, too.

We had four common grade-level assessments made internally throughout the year that mirrored the CAASPP content. We had the students monitor their progress with a monitoring sheet. In their notebook, each student had a protected sheet with the date of the test, their score, and a space for reflection, including their goals, what they needed to do to get better, and if they were satisfied. They could see which areas they needed to work on. If they struggled in a certain area, they were encouraged to come to Saturday school.

Systemic Changes

I had a fantastic principal. When I first arrived, she was the assistant principal. It was the perfect timing of me being so upset but inspired and excited, and she went from assistant principal to principal.

She was trying to shift every department. The following year, she implemented the monitoring piece and sharing data with the students. It became a school-wide effort, rather than just me trying to do that in the math department. I’m so grateful to her, the timing, the school, and the student population.

She is a former math teacher. She shifted things to data driven. Every department meeting, we had to think: “What are we measuring? When are we measuring it? How are we presenting it?” We were not only presenting it in our small group but twice a year (mid-year and end of year) to the whole school.

The principal would say:

“Take risks.

It doesn’t have to be neat.

It doesn’t have to be pretty.

We are learning.

We can’t do things how we usually do it.

It will work.”

The systematic shift encouraged risk taking, student-centered thinking, and data. Maybe some teachers thought she was nuts, but overall, it worked.

You can’t do everything all at once, either. We didn’t implement the student awareness piece that very first year. We did it the following year because we were still growing. That was a task in itself, having the kids organize and keep up with their scores. Everything happened in a sequence.

Some things needed to be tweaked and honed, but it’s actually pretty simple if you think about it. It’s not this complicated thing.

The big takeaway is that implementation matters.

I had to focus on that: ask questions and protect thinking time. Once you find what works, stick with it.

Coalition Building

I’d spent the summer working on my personal projects. I’d had about 6-8 months to internally make the shift. When I returned, I had so much work done.

I was the math department head at that point. A few days before school started, I asked my principal if we could meet. I showed her what I had been working on, and she was excited like me.

But the other teachers had only two days before the start of the school year, and not all the teachers felt the same way. They were like, “What? You want us to do what?” “There’s no way you’re going to get where you need to be in that short amount of time.” There were six of us. About half of the teachers were on board. The other half of teachers thought everything was good as it was. Two teachers thought it would be exhausting. There were two teachers who said it was too much. On top of that, those two teachers were in a very impoverished neighborhood with so many things going on.

One of them really took to the approach – I called her my “Mini Me.”

There were a lot of materials involved. It could get messy, especially with the water and all the little tiles. I understood that. But I thought about how to truly make sure our students internalize the information. There was no guessing.

There was often blame on the parents or the kids. The students were not equipped to do these types of things, but they just needed practice. I remember the teachers would say the students couldn’t get it. The teachers taught it to the students five times over and over again, and they still weren’t getting it. That was a red flag.

I said: “Maybe that approach isn’t working if you’ve done the same thing five times.”

If I had a test where half of the kids did well, I’m excited because I had half of them who could teach the others. Even 25% was great.

There was resistance to the huddles and independent thinking, but it wasn’t as vocalized. It wasn’t until I stepped in the classrooms that I saw it was not happening. There were two things that would happen in these cases:

- Teachers would come visit my classroom or my “Mini Me’s” classroom and watch. She was amazing. She did not play, and she asked urgent questions.

- Sometimes my Mini Me and/or I would model teach in the other teachers’ classes because they said it wouldn’t work in their classroom.

To get a glimpse inside of our classrooms, I did something called “Phone in Pocket.”

We recorded ourselves on our cell phones

and then shared a 3-minute clip in our meetings.

We started a number of department meetings with this to work on our questioning. You would hear the teacher’s questions and ask questions like, “Were there any missed opportunities?”

The big shift in teacher turnaround was because,

ultimately,

teachers want to be successful,

and they want their kids to succeed.

Regardless of if they have a deficit mindset, they genuinely want their kids to do well, and that’s sometimes why they teach the same thing five or six times. It’s because they’re trying. What shifts teachers’ mindsets is when they see their students make gains. That’s why I always ask, “Where’s your exit ticket data? Let’s look at it because it’s proven.”

I remember having one teacher who had the best classroom management ever, but it was too controlled. Those kids could hardly speak. They were too scared to think. The teacher didn’t want to let go of the reigns, but when we did it the other way, she said her kids had never scored that high on the exit tickets before—70% of the kids got it. Usually, she had like 20% get it. The teacher saw this work. She felt successful because her kids were successful.

Some teachers said it didn’t work in their class, but how many times did they try it? Once? I said: “Let’s try it again and get better at it. Don’t just throw it out. It’s good practice.” Sometimes, if it didn’t go according to plan, teachers just thought it didn’t work versus thinking about what could be wrong with their implementation and what they need to fix for the lesson to transpire.

Team Meetings

I was very convincing.

I was already the math department head before CAASPP, but our meetings weren’t as fierce and urgent. I changed our bi-weekly department meetings into real working meetings. We had common small quizzes and common quarter quizzes. We would bring in the data from the assessments and compare it. Then, we would think about it together and say things like: “What are you doing? What do your lessons look like?” We got to the point where we gave each other real, critical feedback, where we had open classroom doors, and we would walk in and see each other’s lessons.

Eventually, the team of teachers were co-crafting the assessment questions. We were choosing and tweaking lessons—that’s when I got teachers from the other side excited about it because they were part of that assessment creation. They were enthusiastic about the questions.

We were really data driven. We would look at the data and reteach what we needed to.

The time it took for me to plan the meetings was so intense. I remember always being pressed for times, like five minutes for this topic and 10 minutes for another topic.

Success Indicators

I knew it was working while implementing. I just knew it.

Students stopped saying:

“You haven’t taught us this before.”

In the past, the students used to say, “We’ve never done anything like this before” when the only thing I did was switch the variable or make it a vertical versus horizontal table.

I asked another teacher if she saw this happening, and she noticed it, too. Students started using their toolbox and stopped following a step-by-step recipe. They were thinking on their own and unpacked never-before-seen problems and made sense of them.

Another indicator was that the students’ level of questions improved.

The openness in the classroom encouraged students to volunteer and share their mistakes and different strategies, unprompted. The goal was to get better and for the whole class community to get better.

We had a student teacher who came for two days. He was very shy. I told him to find his voice. I gave him the lesson, and I watched him teach. My kids weren’t used to a teacher explaining everything. He was teaching by himself.

A student raised his hand and said:

“Can I share a mistake I made?”

Another kid’s hand went up and asked if he could show the teacher another strategy.

My students refused to be taught and just spoken to.

I was like, “My kids have arrived.” I was proud of them. They created space for themselves. And I saw score improvements through the exit tickets and the common assessments.

CAASP Year 2

At the end of the year, although I was exhausted, I told the principal: “Everything is on the table. If our scores don’t increase, I may have to step back. We have done every possible thing we can.”

That second year, we had incredible growth. Our scores increased.

We went from the lowest performing school in the district

to having the highest increase in scores.

That’s when a report came out on our school. They said if we continued like this, we would bypass the other schools.

They did a regression on our school because we were such an outlier. They said we should not be performing like that. We had them come in, and they looked at our department meetings.

They realized the improvements were because of

student data, collaboration, feedback, and practice.

We had folks coming to our school as a lab to see how we run our meetings. My principle and I were asked to share our story with other high-performing principals.

It was the best feeling.

It affirmed that yes, you need a rich curriculum,

but implementation is by far the number one priority.

That’s my story of growth.

Postscript

Charity’s principal, Megan Traver, went on to author:

She acknowledged Charity’s work:

To Charity Rock – for being the ultimate leadership partner in our work at Washington.

Your fierce belief in our school community, ability to inspire excellence and risk-taking,

and brilliant mind made you an essential catalyst in the change we created.

I am so grateful for you.

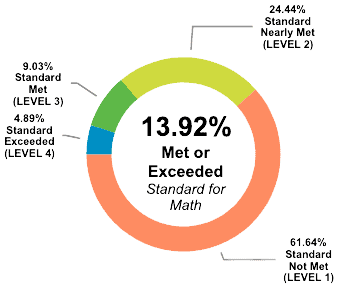

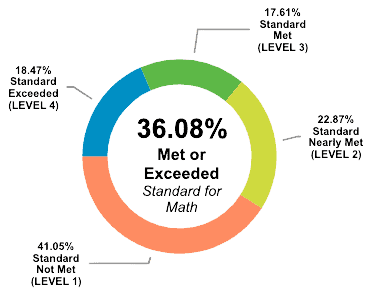

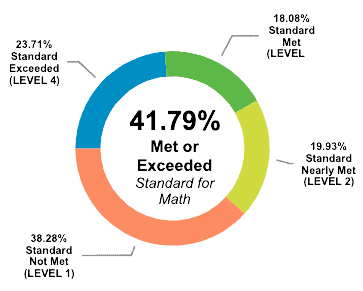

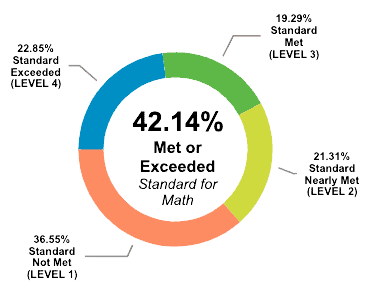

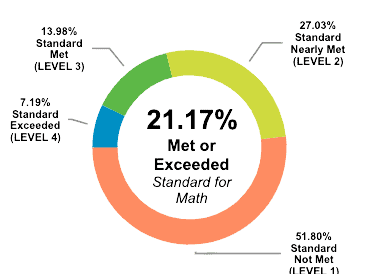

Following their initial success, Washington Middle School mathematics students’ scores continued rising in subsequent years:

Charity transitioned to the role of Secondary Math Specialist at Environmental Charter Schools in September 2019. CAASP was suspended during COVID-19…

and the results were cautioned the following year.

The most recent CASSP assessment was completed at the end of 2022.